This is a talk I gave at Google London last week. Thanks to Matt Jones, Tom Jenkins and Henry Holland for the invite!

So. Hello!

Yep, that’s me.

I’m going to talk about four things today. I’ll start with a look at The Tune Zoo – a music toy for iPad I released a few months ago – then zoom out a bit, surveying it from wider vistas like learning and play, then zoom out even more, and have a think about what design for play might look like in the future. So, here we go.

Yes, I do.

Until pretty recently, I worked at Apple…

…as part of this group.

It’s a pretty small team…

…made up of people who all work somewhere across a gradient from Art to Engineering. Some of us learned to code at design school, and some of us got into design at engineering school.

And this is what the group mostly does. When I started there, about 6 years ago, we were working on prototypes of some things that made it into the world recently…

…like 3D Touch,

and the Taptic Engine.

We also worked on the camera on the iPhone 7 Plus…

the Touch Bar,

Siri on the Mac,

the latest Apple TV interface and Siri Remote,

the Apple Pencil – both the UI, and the algorithms for stroke quality…

…and literally hundreds of other ideas that may or may not make it into the world in future.

I left Apple last year to set up a little design studio…

…called Extraordinary Facility.

It has a small, nimble staff! I literally started it from my kitchen table.

And this is what I’m focused on – building up a little design practice and consultancy, focused on learning and play.

I’m interested in design for learning and play in its widest sense, from little toys and tools, through media, and up to learning environments, like installations in museums. I’d like to say that this is a ‘what we do’ list, but right now it’s more of a statement of intent. We’ll get there!

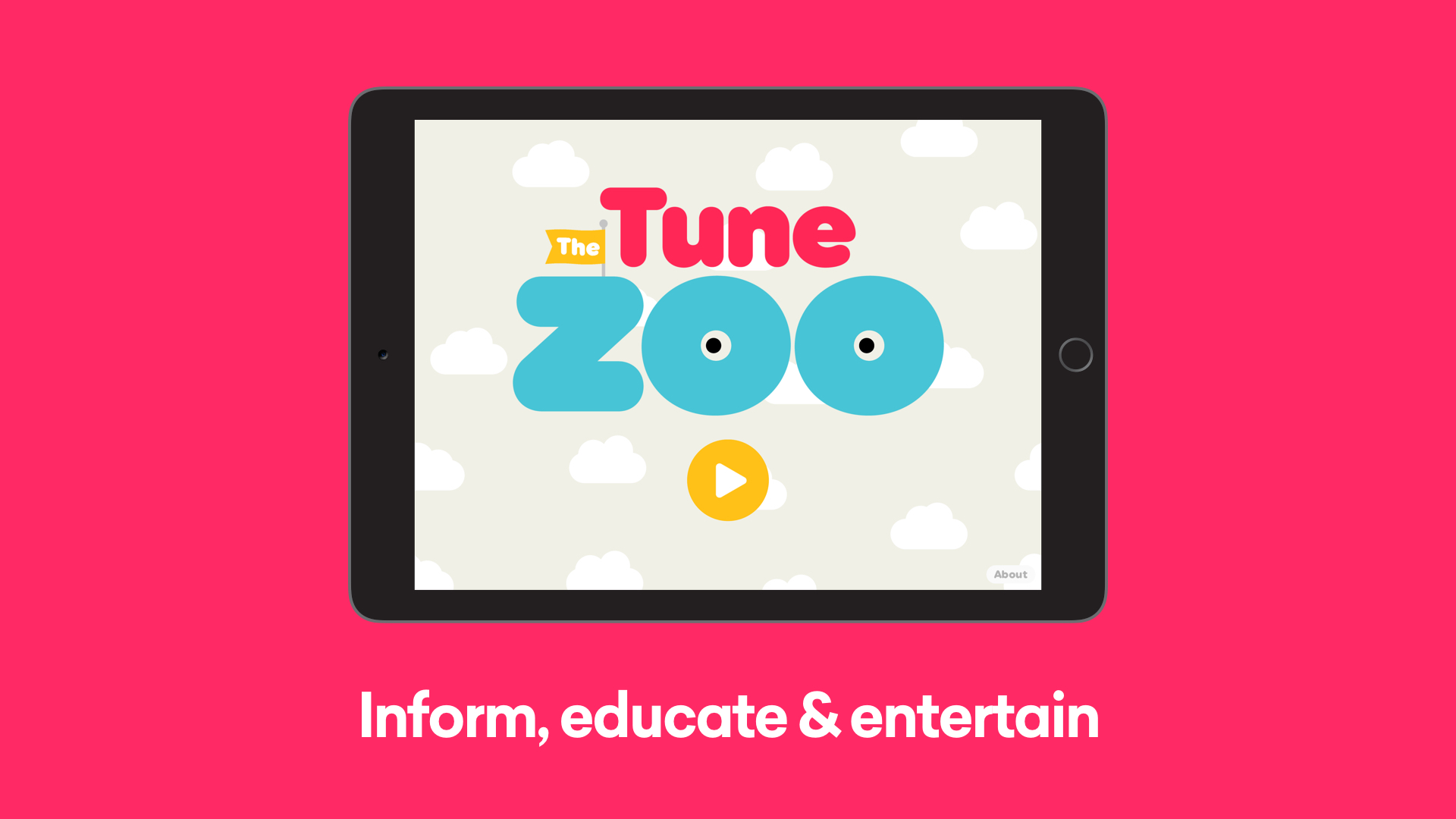

The Tune Zoo – a music toy for iPad – is the studio’s first project. I’ll stop wittering on for a minute or two, and just play you the trailer.

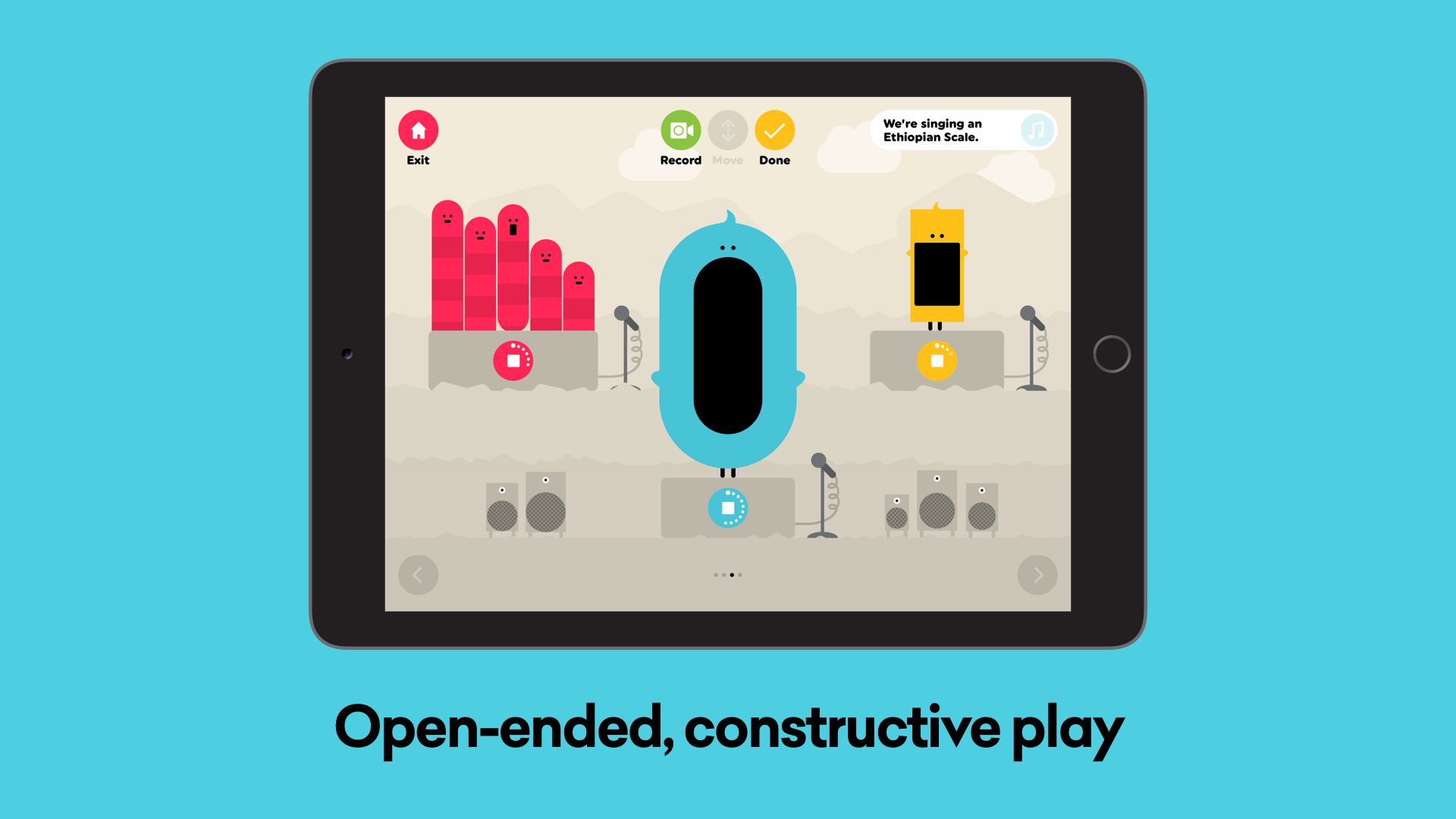

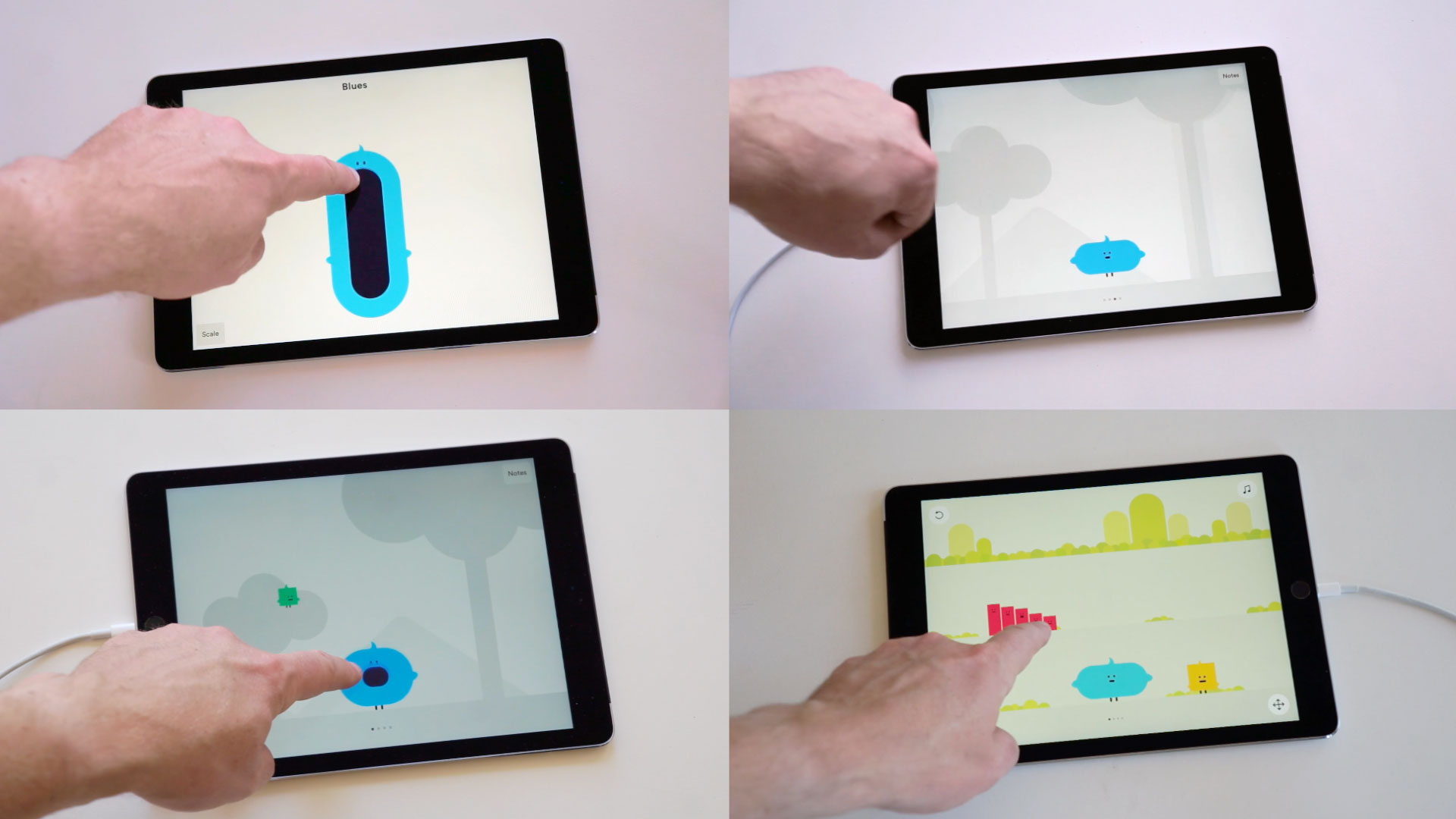

So, hopefully as the trailer shows, The Tune Zoo is exactly that – it’s a place where kids (of all ages!) can wander around, pet some little musical animals and see what they do. Which is – mostly – sing!

There are no goals or high scores – no ‘right’ way to play with it. It’s pretty open-ended, encouraging curious, creative play, exploring things like melody, harmony, rhythm, looping and composition…

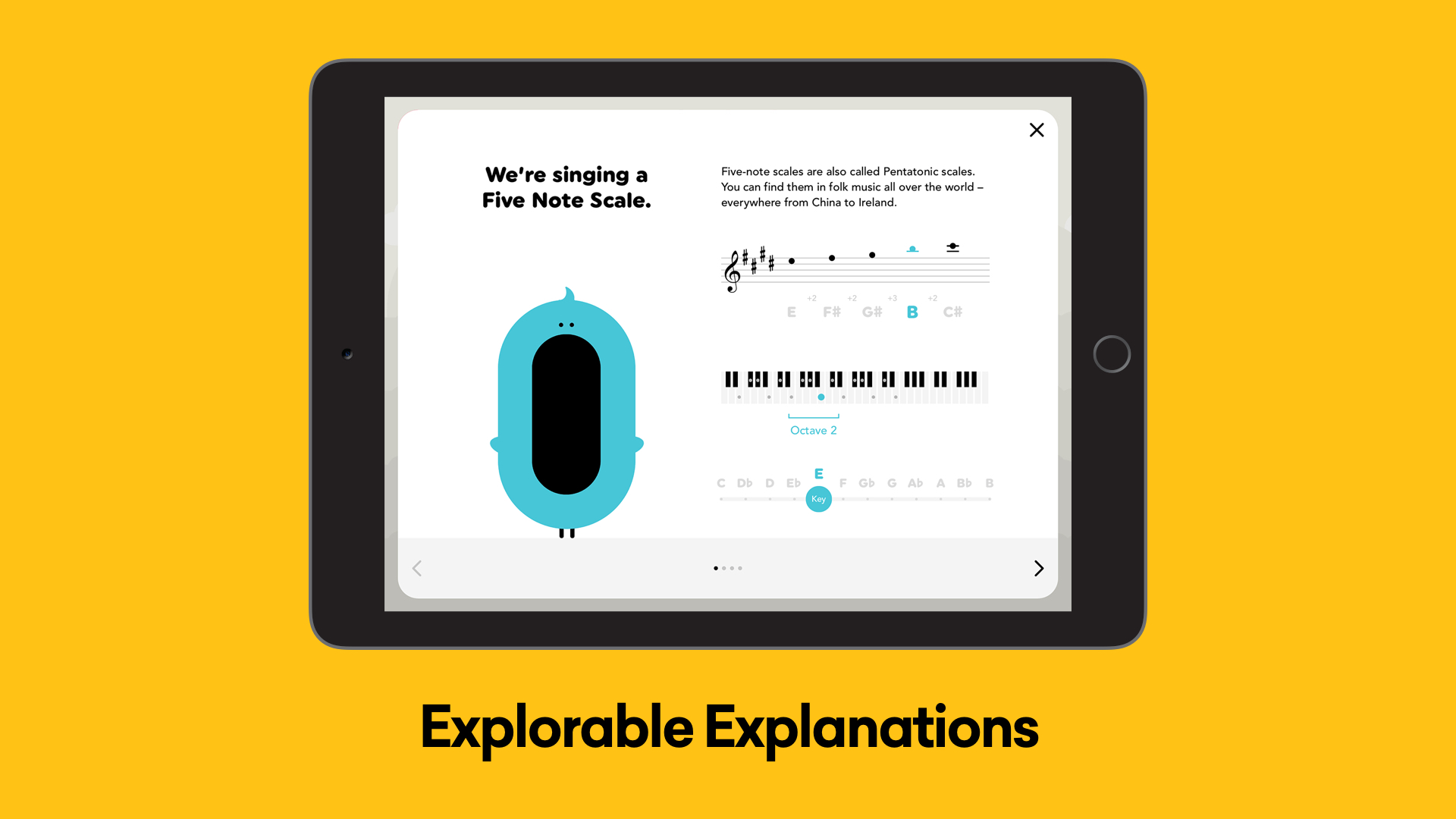

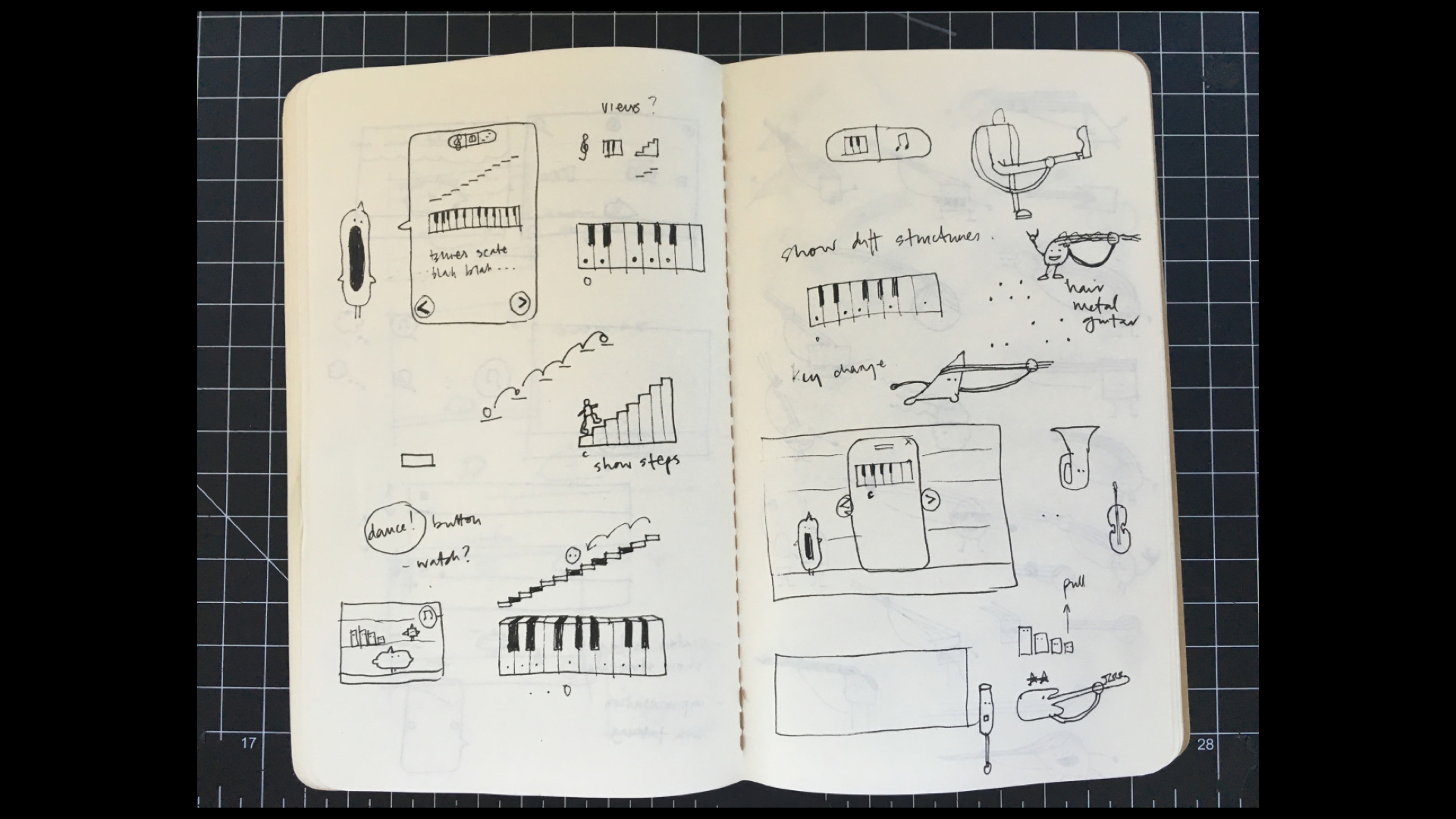

…and is full of Explorable Explanations. This is a little panel you can pull up from anywhere – it shows you what note you’re singing, in what key, as part of what scale, and so on. And, if you can read music, the notation makes it easy to play or sing along.

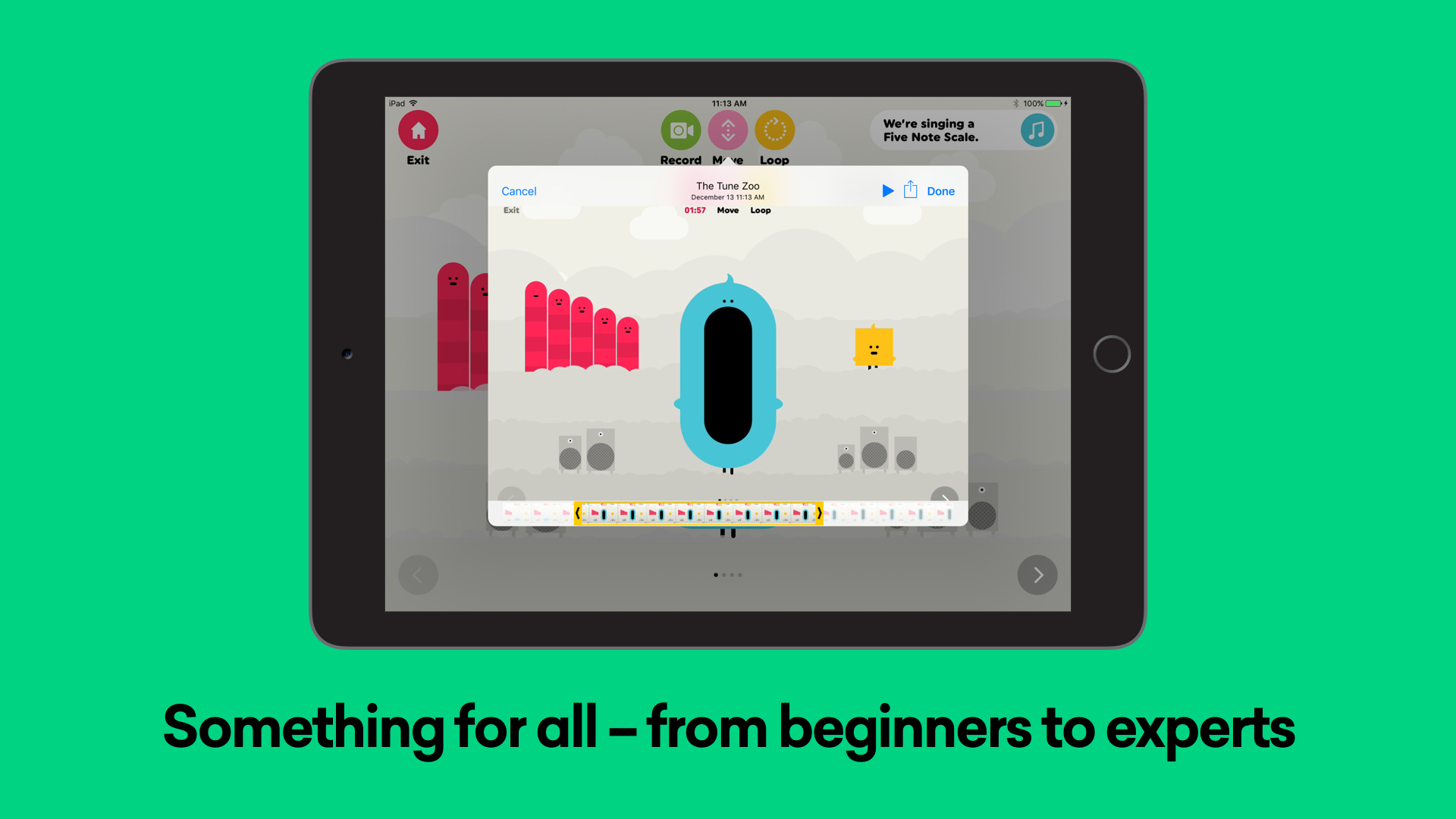

It was really important to me that The Tune Zoo gives everyone – from beginners to experts – the possibility of playing together. I could imagine a kid making the bird sing, as their jazz-loving grandad jams along on his guitar or something. I should really make a film of that! Hmm.

So, where did I get the idea for The Tune Zoo? Well, I think it starts about twelve years ago…

…at one of London’s main creative oil rigs, the Royal College of Art, where I did my masters in Interaction Design.

This fellow was one of my tutors. His name is Durrell Bishop, and, for my money, is one of the most influential designers of his generation. He’s been teaching at the RCA and all over the world for years now, helping launch the careers of some of the best designers around today, as well running his own experimental practice.

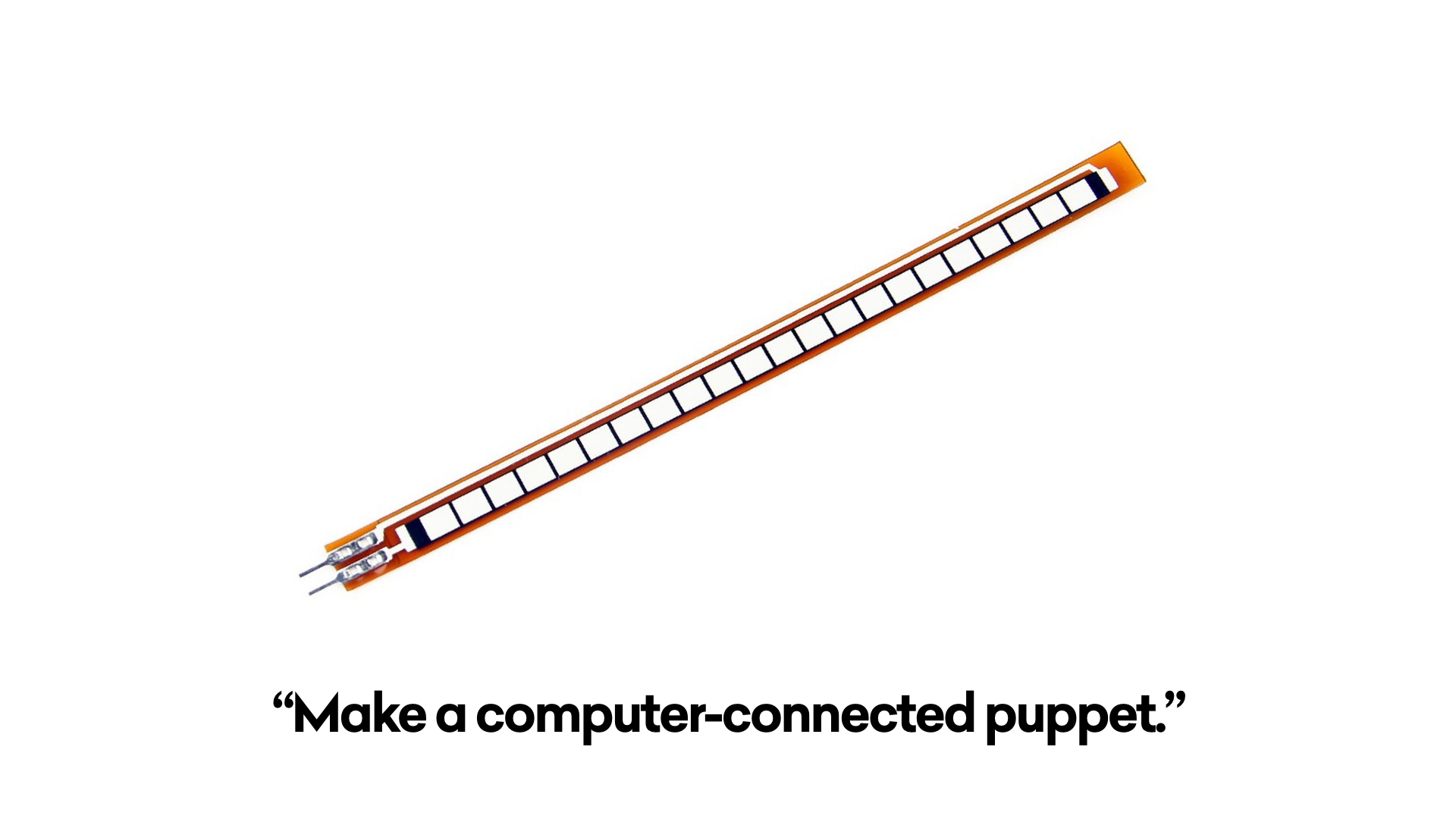

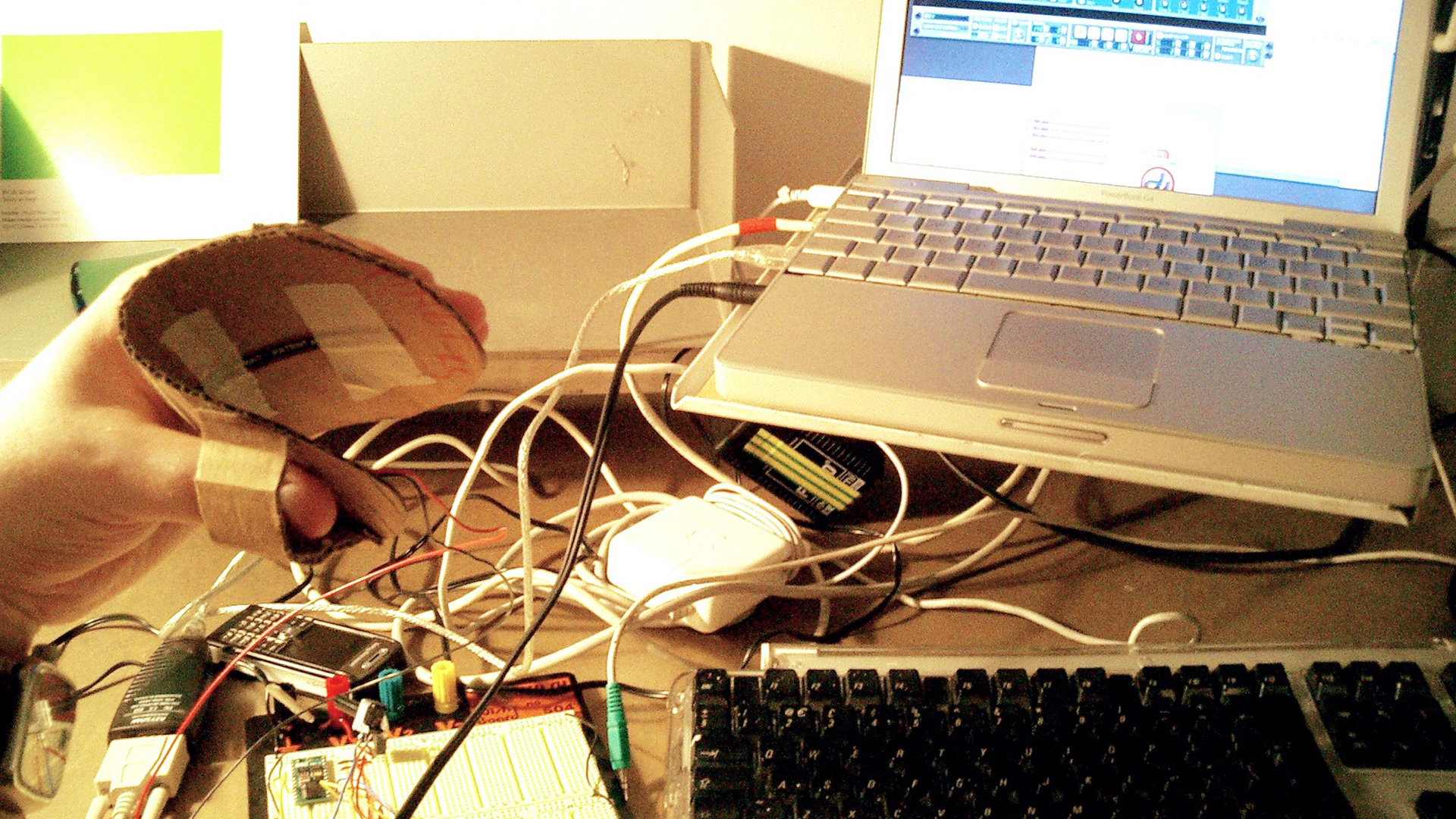

This is one of the projects he sets. I mean, this is literally it. One sentence! You’re given an electronic component, picked from a hat – an air pressure sensor, a proximity sensor, a flex sensor, or something similar – and told to go off and make a puppet with it. It’s a deceptively simple brief: you’re dealing with “digital as material” – learning how to wire up sensors to microcontrollers, getting them to talk to a computer and so on – while exploring puppetry, and all the ancient traditions of storytelling and play that taps into.

Look how long ago this was! – there’s an old Sony Ericsson phone on the table there. Wow. Anyway, I was given a flex sensor. I taped it to a piece of cardboard, did some basic electronics tutorials, and ended up managing to get the bend values piped into some music software over MIDI. Close the mouth a bit and you sing a low note, and open it up wide to sing a high note.

Then a little creative spark brought everything to life. I mapped the sensor values to a Blues scale, put on some background music to jam along with, and suddenly this mess of wires and card transformed into a silly grin-inducing toy. I wrapped everything in a sock puppet, and bam. Done.

This is Brigitte, who at the time was the course administrator, and therefore chief project guinea pig. Here, she’s having a go on the first prototype. I spent the next year and a half of my masters trying – and failing – to better it.

After college, I kept the puppets going as a side gig, continually tinkering with them, showing them at festivals, conferences, kids’ events – watching and learning as people played with them.

Then, last year, when I left Apple, I decided to start Extraordinary Facility, and focus on the project full time for six months. I wanted to see if I could make a screen-based puppet in a little app, and put something out in time for Christmas, doing everything myself – design, animation, code, sound design, background music and so on – you know, the classic indie developer story.

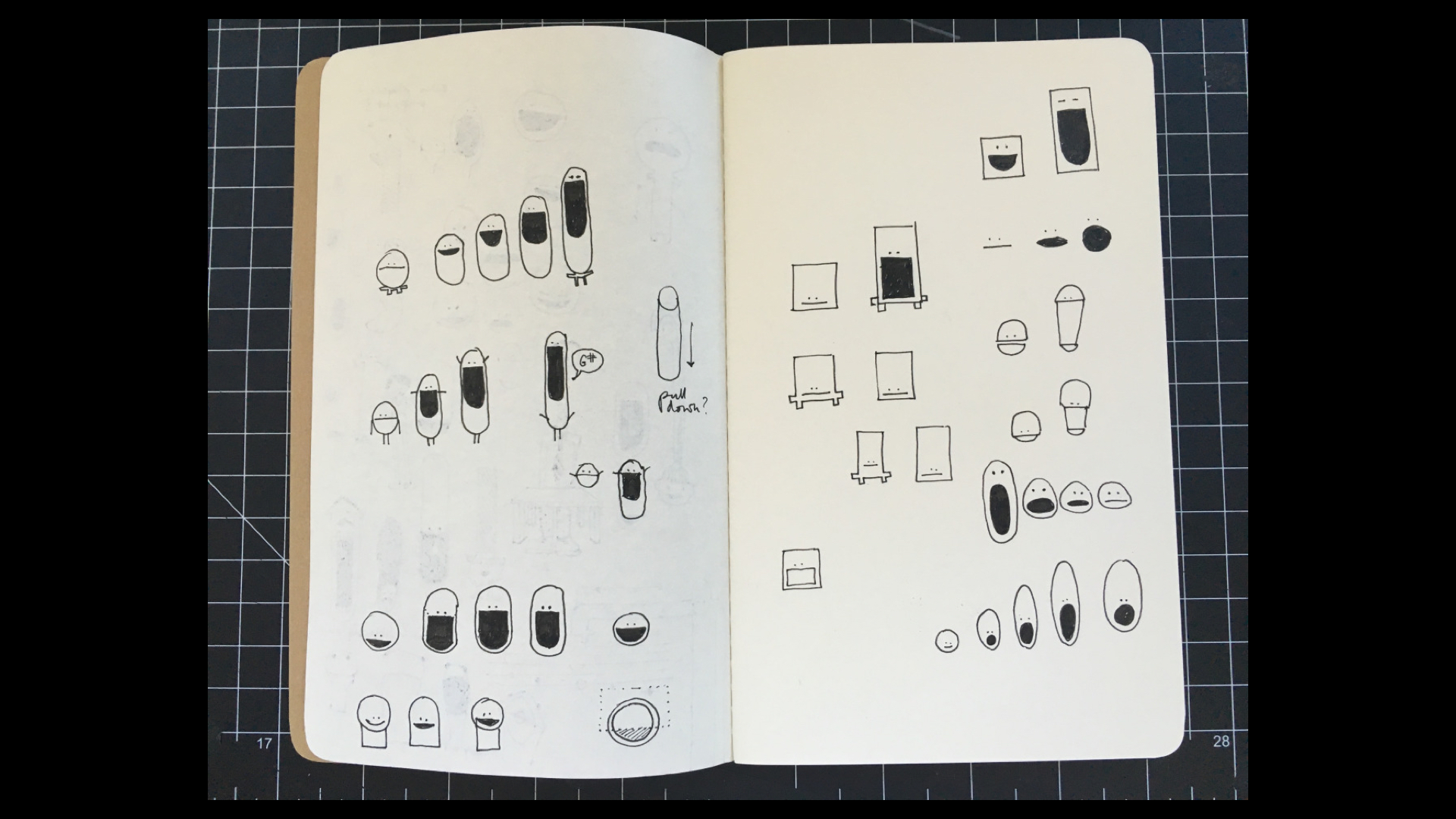

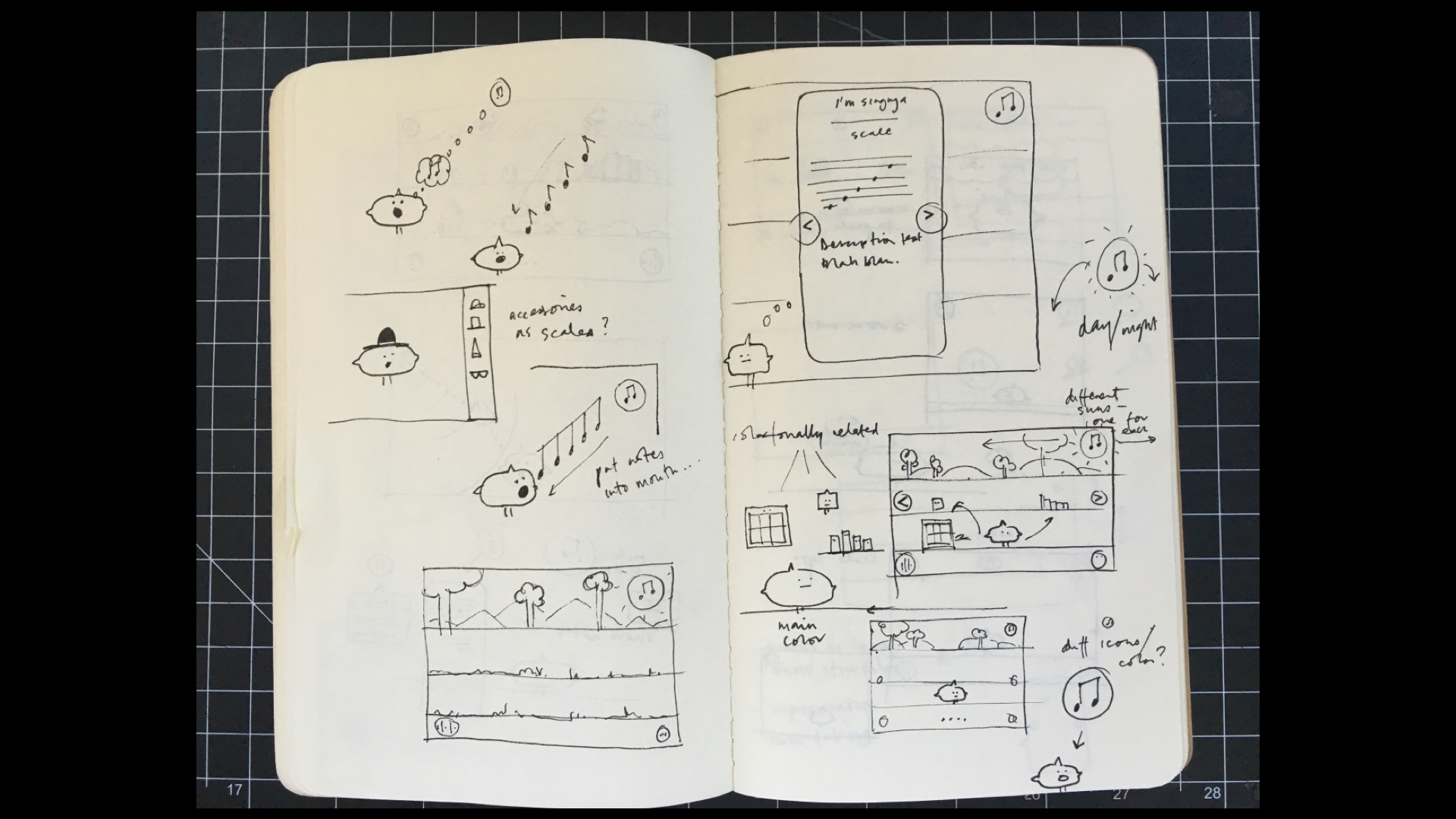

This is where I started – thinking about simple touch gestures like swiping and dragging, and how they could work like a sock puppet. You can see the stretchy head idea emerging here…

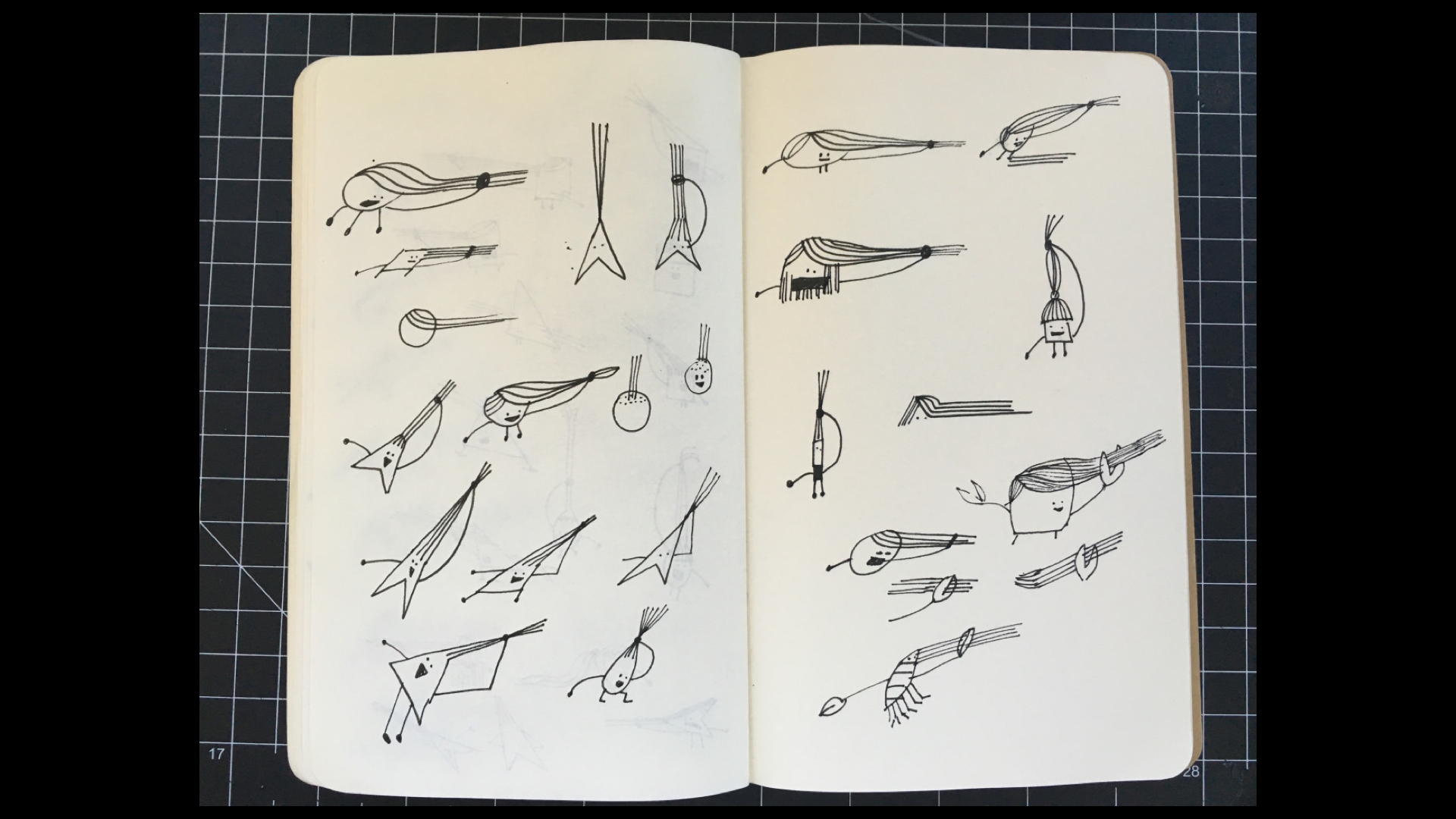

… then there was some sort of guitar character that, er, uses their own hair as the strings. I don’t know! It just comes out of the pen sometimes.

Here I’m getting a bit more purposeful – working out the beginnings of the explorable explanations for scales…

…and here you can see the little ‘scale world’ idea start to emerge.

I sketched a lot in code – in Swift, hooked up to libPd, where I handled all the sound and music – getting the basic behaviors working, thinking about landscapes, other characters and so on. I didn’t really have a set plan – all the ideas emerged by making prototypes and playing around with them. I’m a huge believer in making as thinking – in letting the material qualities of stuff (whether it be physical or digital) guide form and function. You can see more of this stuff in the development notes.

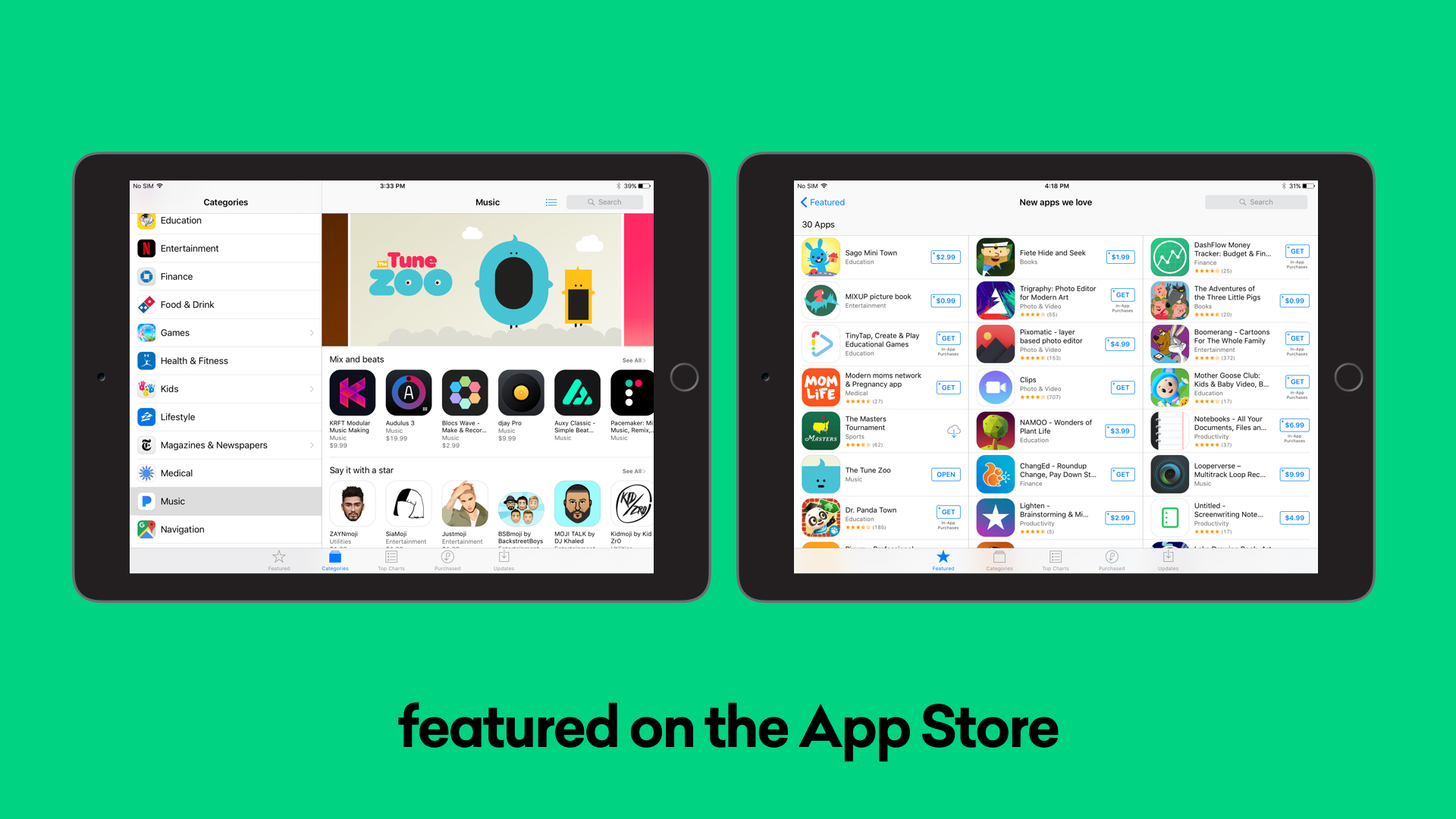

And, as intended, I got version 1.0 out just in time for Christmas last year. It’s been doing ok!

It got featured on the App Store recently, as part of the Music category and “New apps we love” collection. Not too shabby.

So, what am I up to now?

Well, I’ve been working on growing the studio, and making some prototypes of new ideas. I put together a little event about a month ago, where people and their kids came along and had a play with the work in progress.

You learn so much by building some quick, scrappy prototypes, and watching people play with them. The key thing to look out for is fun – are people smiling, laughing, or fighting over who gets the next go? Once you see that, you know you’re on the right track.

It’s also a great excuse to just hang out with your friends.

Here’s a peek at how The Tune Zoo might evolve in the near future. The sock puppet idea has returned! This time as a character from the app. You sit in front of a camera, and see yourself inside the Tune Zoo landscape, with all the other characters around you on screen. Again, it’s just a prototype at this point. We’ll see how it develops.

Kids are by far the best playtesters – they’re completely (sometimes brutally) honest about whether something’s fun or not. And you can see, on the right there, some little clipboards I left around the space, for people to leave written feedback if they wanted to. This was just an experiment, but worked pretty well – I got tons of thoughtful, useful notes, as well as messages of encouragement. Nice!

So, maybe this is one way of describing how Extraordinary Facility works. The more playful the process, the more playful the outcome. This seems like common sense, but I think it does take a certain discipline. It’s about firstly breaking an idea down to its component parts, and playing around with them to find something fun – say, a tiny detail in the way something behaves, a line in a piece of communication, or the way you move around an environment. Focus on the fun first, then let that guide the rest of the design process, framing form, function and so on.

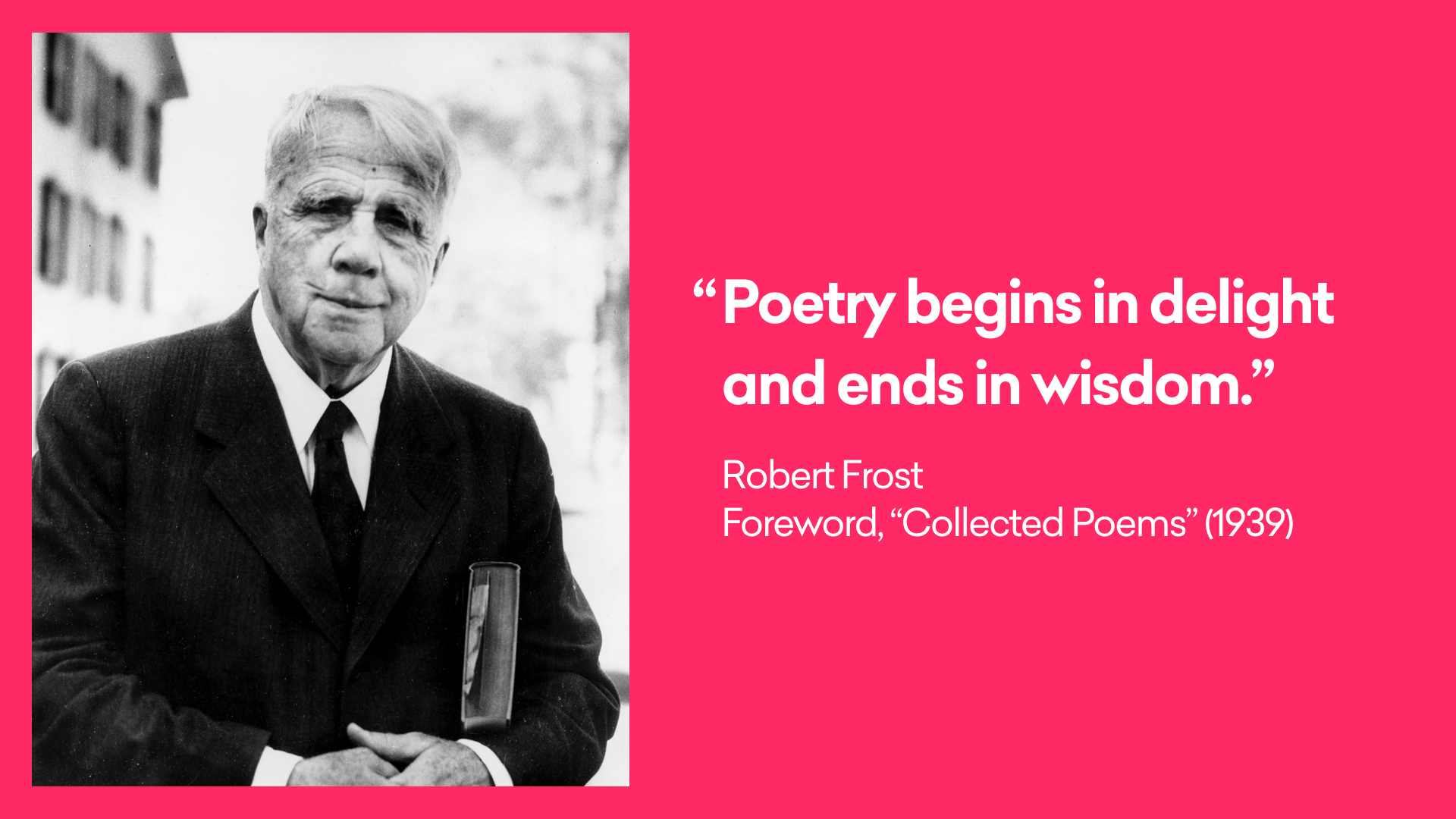

Robert Frost once said that poetry “begins in delight and ends in wisdom” – perhaps we could say the same thing about good design…

…which brings me to my second point!

Why am I so interested in this?

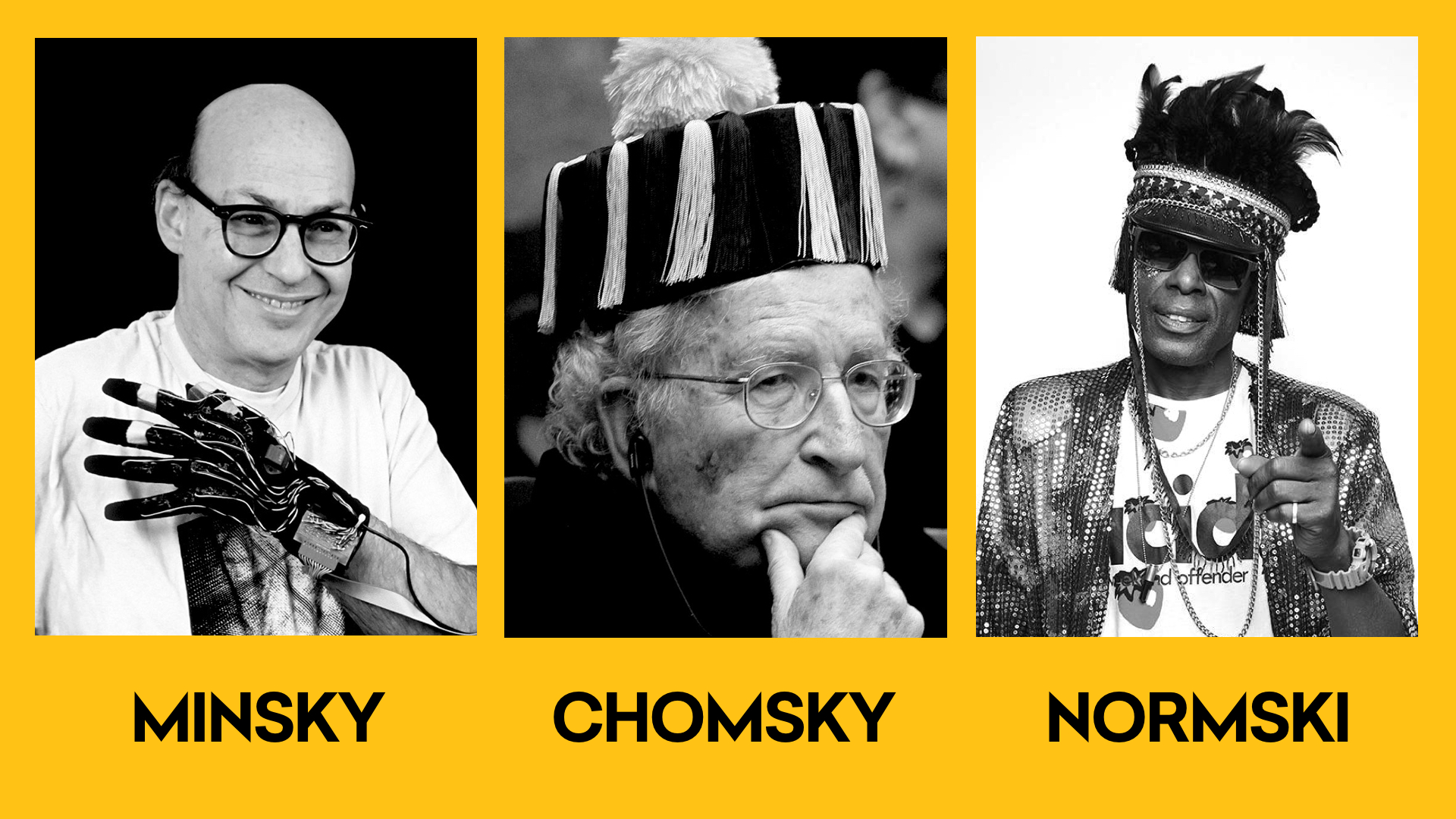

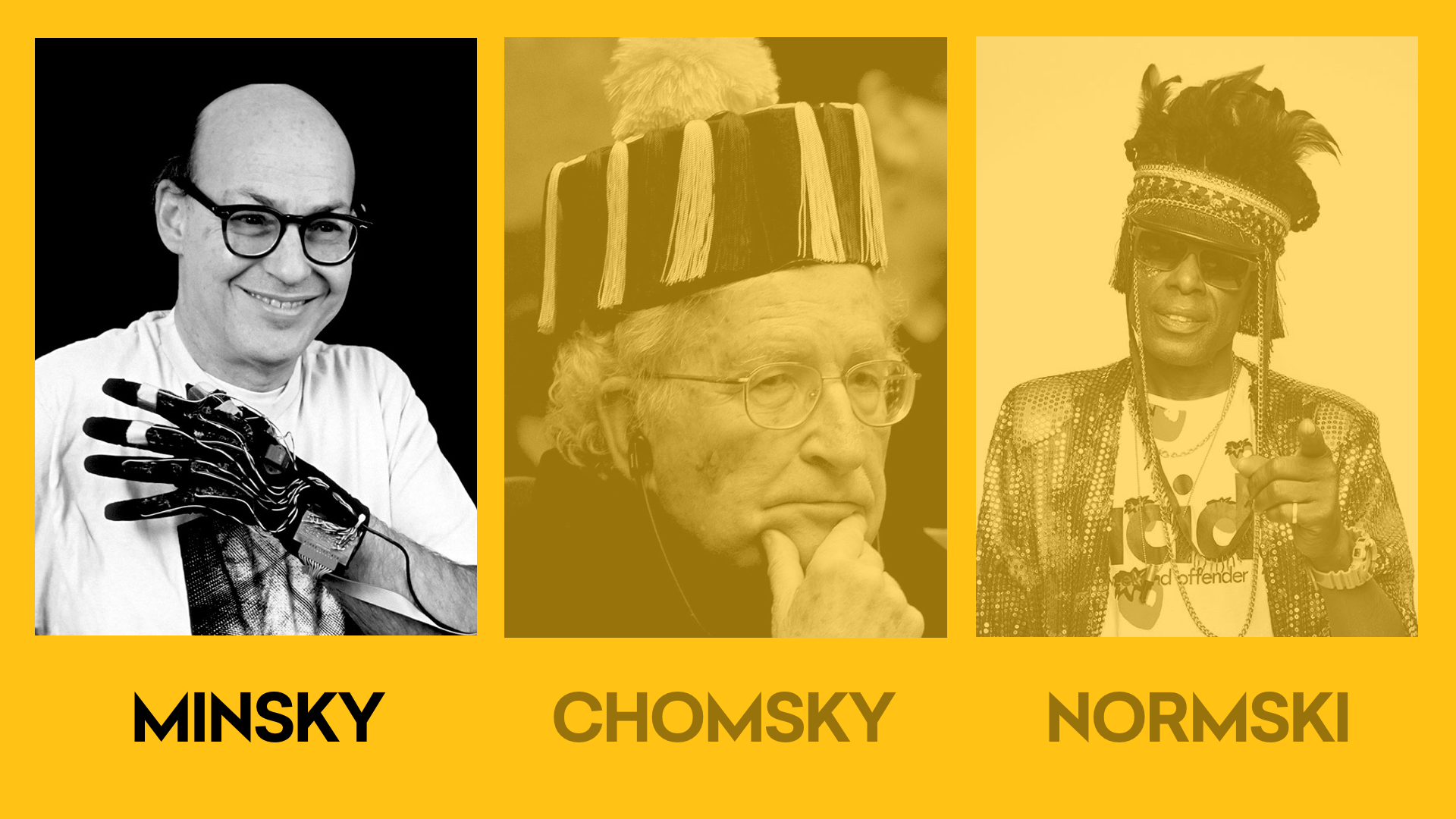

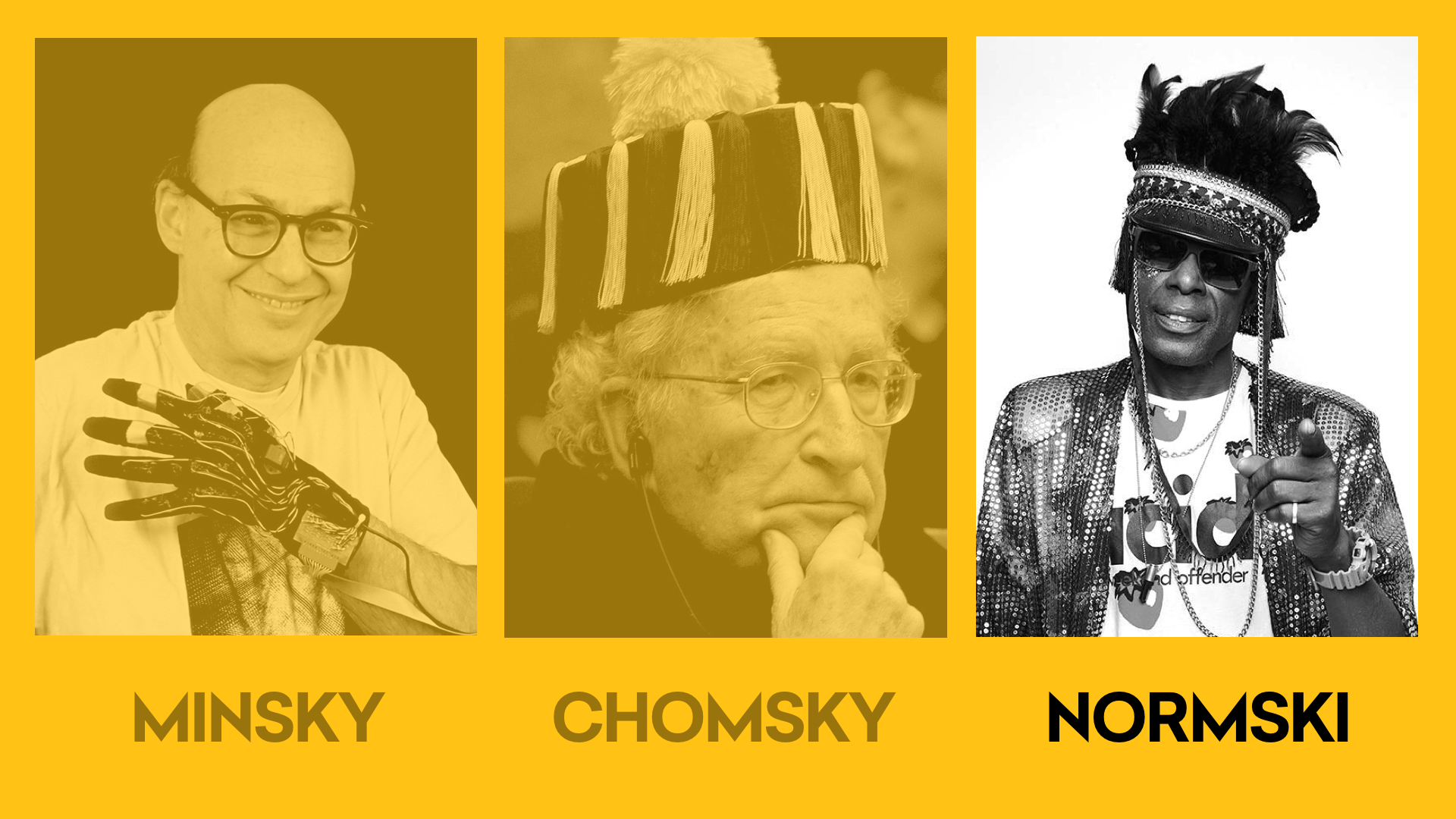

Well, maybe it has something to do with this lot. The finest boy band that never was! Can you imagine?

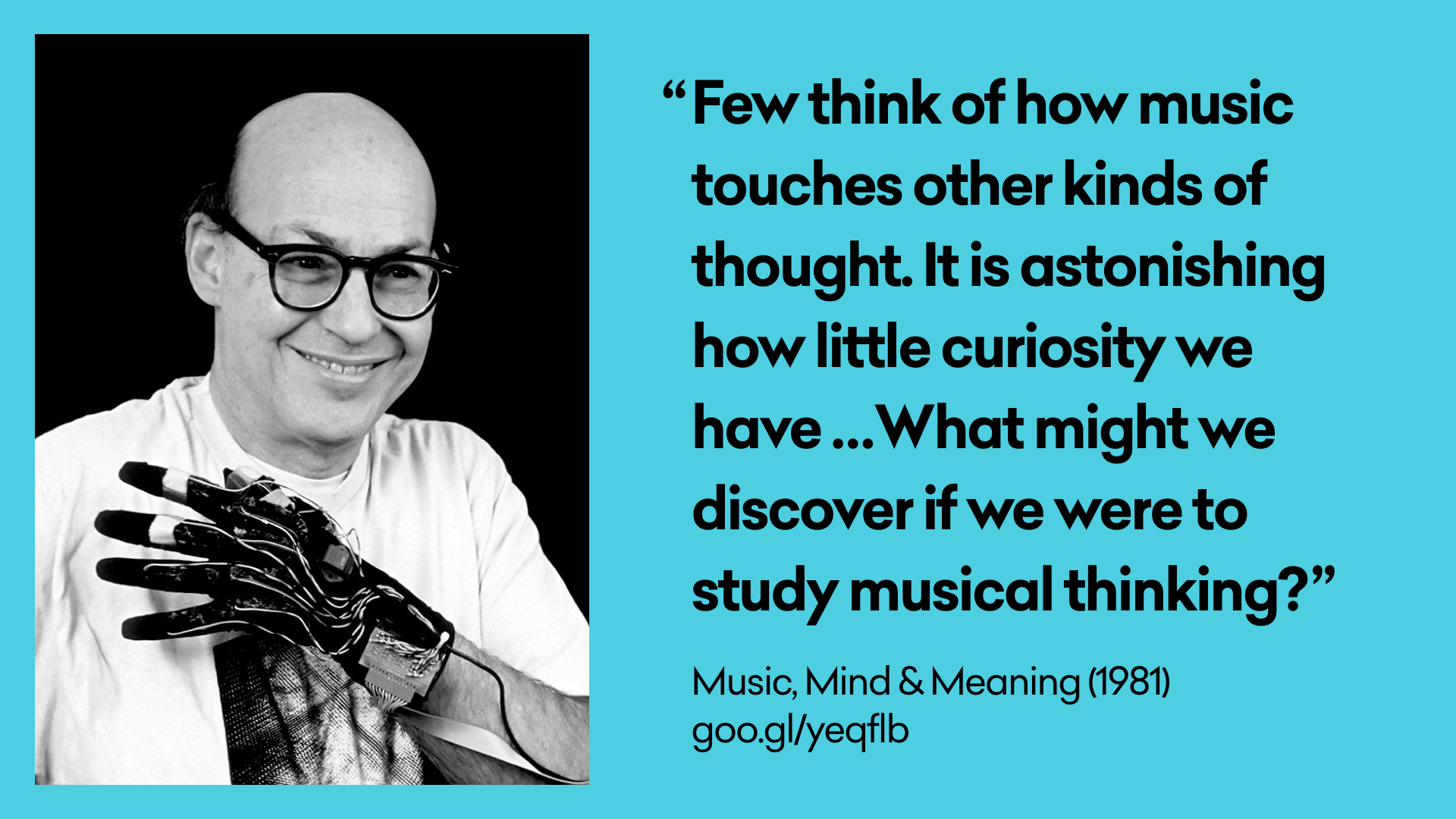

Let’s start with the legendary Marvin Minsky – cognitive scientist, co-founder of the MIT AI Lab, generally regarded as the founding father of AI, as well as an accomplished musician.

If you’ve never seen him improvising fugues on the piano, you should. He also wrote this fantastic paper, Music, Mind & Meaning, in the early 80’s, which I think I read for the first time at college, and have been dipping into ever since. There’s a PhD in nearly every sentence.

A lot of what Minsky discusses in the paper points at Plato…

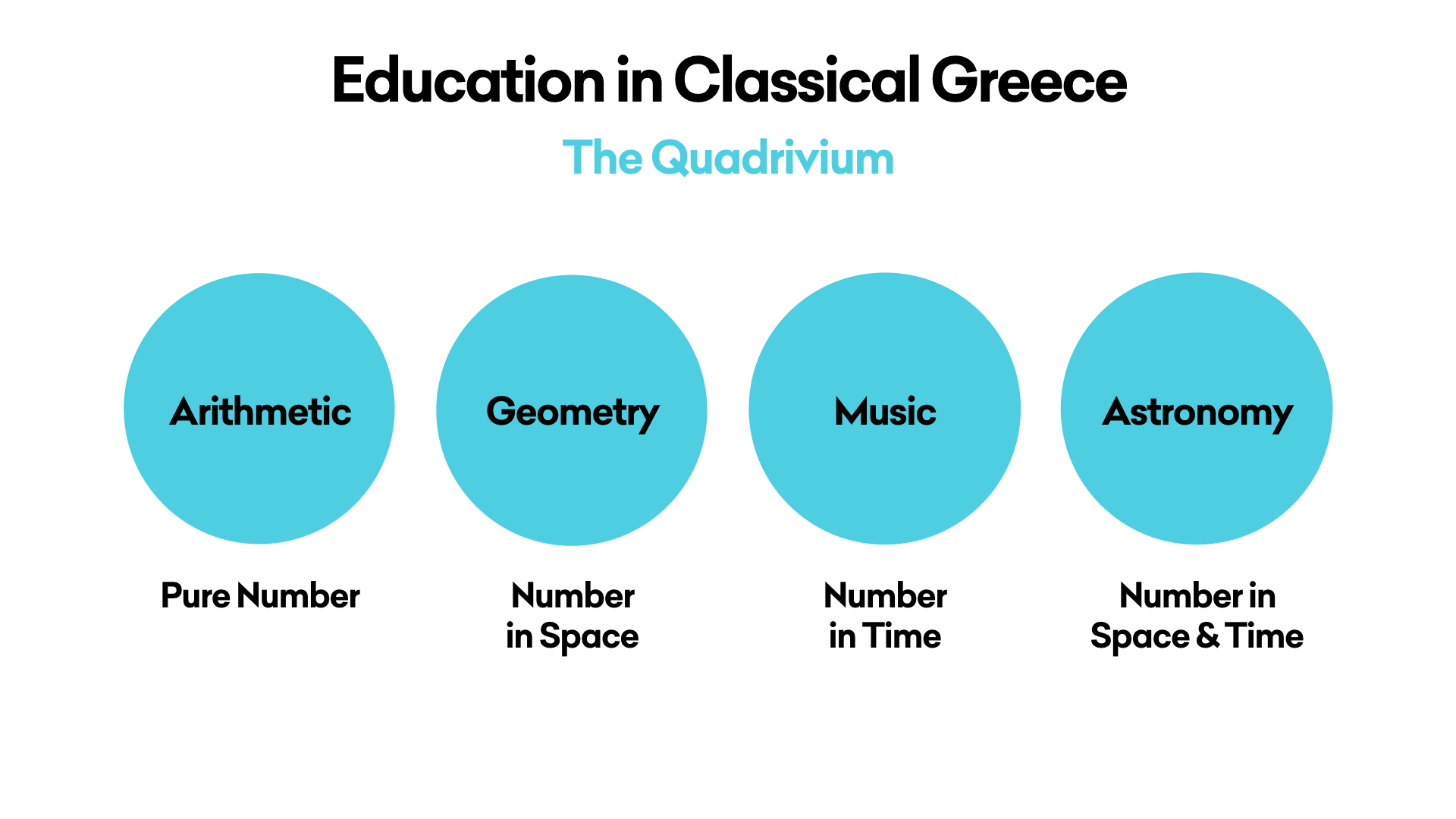

…who, I believe, was one of the first to document the Trivium and Quadrivium, the foundational subjects orbiting Philosophy, an education model which I suppose most (rich, male) ancient Grecians would have been put through. And look – there’s music!

It seems that, as part of the Quadrivium, music was studied more as a branch of of mathematics – as a way of exploring number over time – and less as a form of artistic expression. But, throughout history, as Minsky discusses, we see that much of the power of musical thought is derived from its position right at the center of the overlap between the arts and sciences. I’d make a hefty bet that music has more conceptual connections (and therefore adjacent possibles) than any other form of knowledge – and maybe that’s why I’m so interested in making music toys.

There’s a heap more about it in this book – Music and the Making of Modern Science, by Peter Pesic. It discusses how many developments in science over the last millenium – from cosmology to color theory, irrational numbers to relativity – have foundations in music. Brilliant stuff.

Who’s next? Right. Noam Chomsky – linguist, cognitive scientist, educator, activist, and probably the foremost public intellectual in America for the past 50-odd years. What has he got to do with design for learning and play?

Well, this is a great quote from a great article where he discusses what it means to be truly educated. I think this might be as close as I’ve currently got to a mission statement for the studio.

(Chomsky’s actually quoting this guy – Wilhelm von Humboldt, the father of the modern higher education system – but, uh, I couldn’t make his name rhyme with Minsky and Normski.)

In this treatise from 1793, von Humboldt discusses what he sees as the true purpose of education, and it’s startling how little the argument has changed today.

This is a terribly sweeping summary, but I’d say the treatise broadly comes down to what we think education is for – is it about preparing us for a life of work, or should we pursue it for its own sake – for its innate value to our lives, and the world around us? Ask any teachers you know, and I bet you’ll hear a very similar debate.

So, there are clear links between the purpose of the Quadrivium and the ideas of von Humboldt…

…then between von Humboldt and Chomsky, himself a renowned educator. And I’d say that these are some of the guiding lights of Extraordinary Facility, in terms of what I think the studio should stand for, and the values I’d like to see embedded in the work it produces. But – why not just go and be a teacher? Why set up a design studio to pursue all this? Well, one way of looking at that might come down to this guy – Normski.

It’s probably fair to say that Normski was a key part of British pop culture in the 1980s and 90s. I was around ten years old back then, and remember being completely transfixed as he fronted shows like DEF II and Dance Energy, usually broadcast in the early evenings on BBC Two. He would travel around the country, giving me and millions of other suburban kids our first glimpses into emerging music scenes and street culture. In many ways it’s classic BBC – equal parts Inform, Educate and Entertain…

… and it was broadcast on weeknights at 6:30pm on mainstream TV! It’s hard to see now, in the age of YouTube, just how forward-thinking it was, but for this, I’d put Normski (and producer Janet Street-Porter) up there with Attenborough…

…and say that Def II and Dance Culture represent the BBC at its best.

Inform, educate and entertain – also worth stealing! I think this is why I see a design studio as a good platform to explore learning and play. It can operate fluidly between them – from helping improve products, services or environments for teachers, through to things like the design of museum exhibits, and also encourage casual, informal learning with well-designed playgrounds, toys and games.

And I think The Tune Zoo takes a small step towards that – by taking information and knowledge (like musical language), and making them more “playable”, perhaps we can increase the likelihood of kids joining more dots between more ideas. It’s a start, I guess!

So let’s dig into play a bit more. What is it? Why do we do it? How does it work? We at least know that it’s a human universal across culture, society, language and behavior…

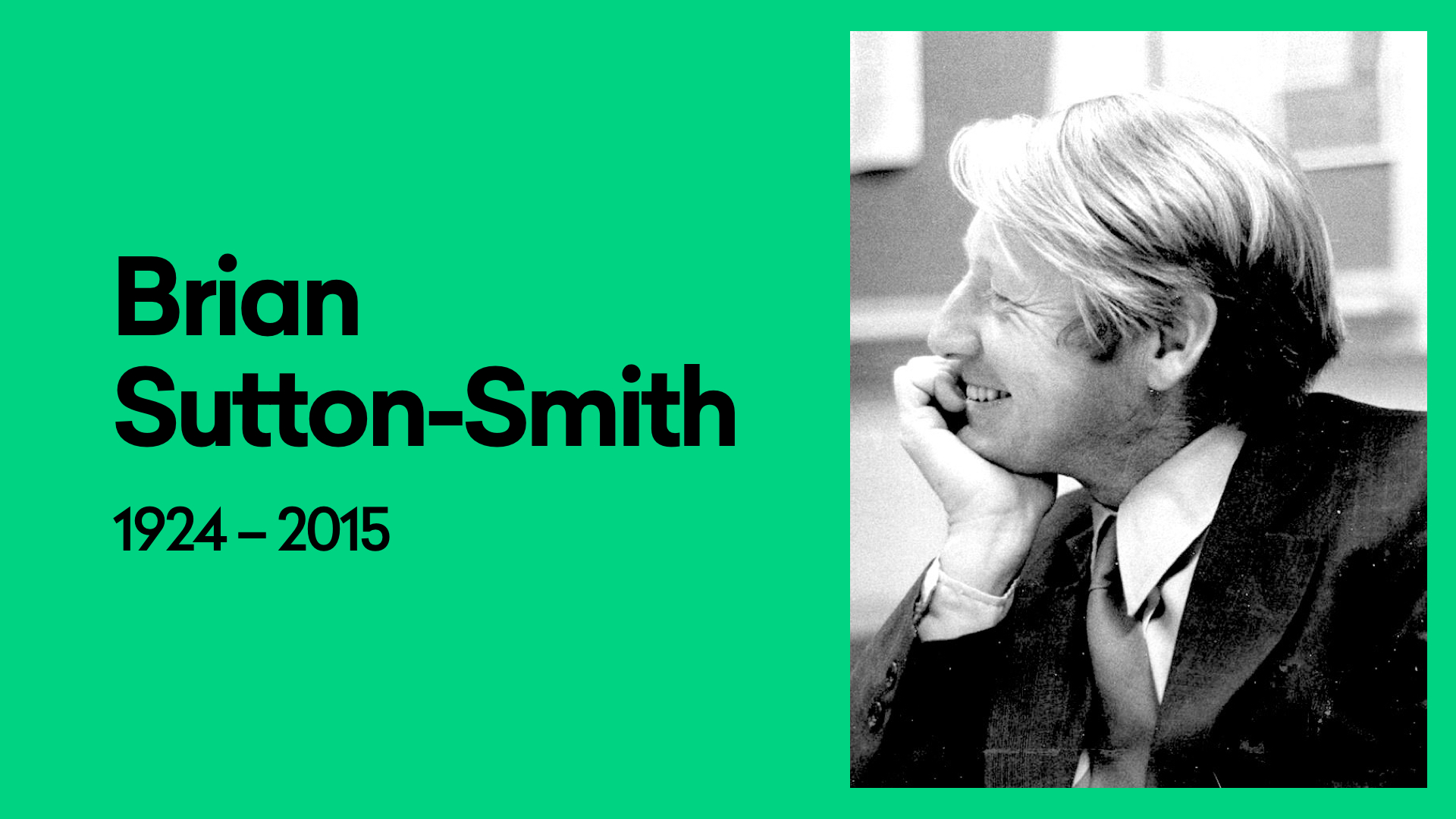

…and when you start digging into play theory, you soon run into this guy, Brian Sutton-Smith.

One of his books, The Ambiguity of Play, is a fantastic primer, dipping into what he calls the “Rhetorics of Play” – the many stories we tell ourselves about what play is and means.

There are roughly seven of them. Big themes! I think The Tune Zoo taps into three of them in particular:

- Play as progress: as learning and development, or preparation for adulthood. Most educational toys embody this view.

- Play as the imaginary: as free-form creativity and expression. Musical play, in particular improvisation and composition, feels like it fits here.

- Play as frivolity: as a form of absurdity or surreality. I think a key quality of The Tune Zoo is that it’s as silly and nonsensical as it is useful and instructive.

The thing that interests me the most about play – both in theory, and just looking around at everyday life – is that it’s so ancient and deep-rooted, as (according to Sutton-Smith) “a major form of pre-linguistic communication in animals”…

…but that the world’s most eminent scholars still can’t agree on what play actually is.

Which, for a designer, makes it a fantastically ripe area to work in.

It seems we’re in good company here. There’s a great bit in Richard Feynman‘s brilliant book The Pleasure of Finding Things Out where he’s in the student canteen at Cornell, watching a guy messing around, throwing a plate in the air. The logo on the plate appears to be rotating faster than the plate is wobbling – so Feynman starts fooling about with equations, working out why, and that eventually leads him to a body of work that wins him the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1965. Talk about play as progress!

Author Philip Pullman’s fantastic article in the Guardian a few years back follows a similar path, imploring teachers to worry more about playfulness than grammar. So, as long as people like this talk about the value of play, that’s enough to keep me focused on it.

So, to the future!

What might play mean to us in the future? Maybe the robots will do all the jobs on the planet, and we’ll be basking in the viridian glow of Universal Basic Income and Fully Automated Luxury Communism. What will we do with our time? Perhaps designing for play will start to take on a slightly different hue…

And of course one of the main cultural expressions of where AI is headed has always been – yep, you guessed it – play.

Perhaps it all points at this tricky term – I’m still unsure as to what it really means, but it’s a useful hook to start thinking about designing for play in the future. Are we already living in post-industrial society? I doubt the world will come to an agreement on that any time soon…

…but it seems to me that some of the world’s most future-facing companies have already put things like play at the center of their business. Snap’s decision to position Spectacles as toys was brilliant. Some may see them as the latest flowering of the Surveillance-Industrial Complex; others may say they’re a fad, and will come to nothing. Either way, the fact that they’re toys seems to free them from many of the usual expectations and connotations. So, maybe we’ll be designing more for idleness than productivity…

…or perhaps everyday life will get closer to some of the ideas of thinkers like Dunne & Raby. For years now, they’ve been at the forefront of using the tools and techniques of design to go beyond its traditional role – as a servant of industry – and speculate about stranger, messier, more complex, more human futures than the sleek, simple, TED-addled corporate visions we’re currently subjected to.

Their ideas tend to find form firstly in specialist books and galleries, but eventually start to osmote into the everyday. It feels to me like the gaps between even the strangest design fiction and contemporary life are glooping together in ever faster, weirder ways. Given the events of the last year, I wouldn’t rule anything out!

But this is the type of peek at the future I get most excited by. A future with AI as a companion species, one we’re currently getting to know primarily through play – like making images together, writing weird movie scripts together, and here, jamming on the piano together. This one’s by a colleague of yours – it’s Yotam Mann’s AI Duet – someone tell him I’m a big fan!

Yotam’s made all the code from AI Duet open source too… hmm, I feel some more prototyping coming on!

So, that’s it! I think I’m out of time.

Thank you for yours! And thanks again to Matt Jones, Henry Holland and Tom Jenkins at Google London for the invite.